Fleming was a Nobel prize-winning scientific mind and had a genuine appreciation of art.

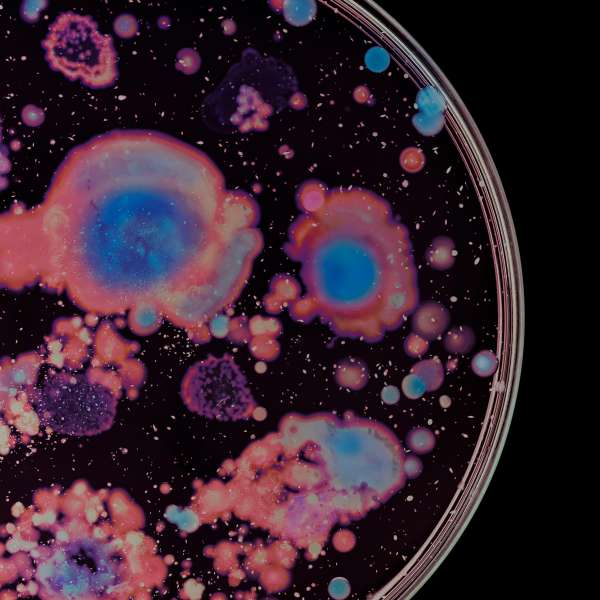

Fleming was not only a Nobel prize-winning scientific mind, but he also had a real appreciation of art. Quite a capable artist himself, having a watercolor hung by the Royal Society of British Water Colour Artists, Fleming also experimented in the lab with pigment-producing microbes. Culturing these color-producing micro-organisms on Petri dishes, Fleming created a range of images, from boxers in a ring to a mother bottle-feeding a baby. This required not only manual dexterity but also the balancing of the growth of several micro-organisms to produce the right pigment in the right quantity and place at the right time.

Nobel Prize laureates of 1945. From left Artturi Virtanen, Chemistry, Alexander Fleming, Medicine, Ernst B Chain, Medicine, Gabriela Mistral, Literature and Howard Florey, Medicine.

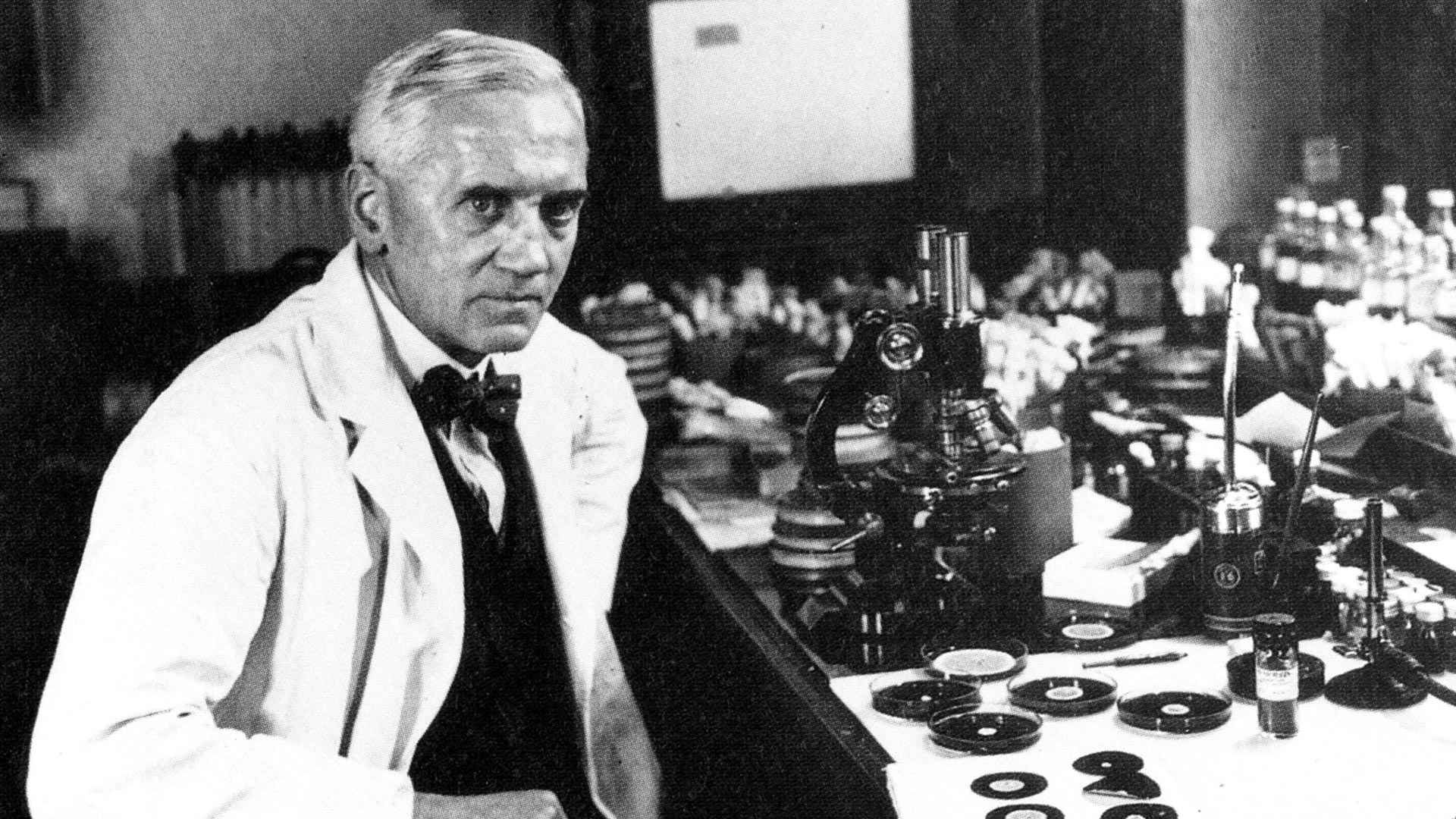

Sir Alexander Fleming, Scottish biologist and pharmacologist (1881-1955) at St Mary's Hospital, Paddington, London.

Sir Alexander Fleming chaired as the newly-appointed Vice-Chancellor of Edinburgh University in 1952

These renderings didn’t necessarily appeal to everyone, however. Allison recalls that Queen Mary, grandmother to the current Queen Elizabeth II, “was not amused and hurried past” when shown these works1. Nonetheless, this art survived, with examples of these bacterial paintings still possible to be seen at the Alexander Fleming Museum at St. Mary’s Hospital in London.

Perhaps the most interesting anecdote relating to Fleming’s eye for art is that of VD Allison’s purchase of three etchings at a Sotheby’s auction. Following Fleming’s suggestion to “Try £3”, Allison won the lot, taking home a small collection of works of the then-unknown Pablo Picasso. He was later able to sell these, as we would expect, for “a considerable profit.”

From 3p for tears to £3 for Picassos, Fleming’s eye and contributions had an immeasurable impact on medicine and science in the 20th century. For this, he was knighted in 1944 and co-awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1945. To conclude our first installment, we leave you with part of his acceptance speech2,

__

“For many years, I have read of people getting the Nobel Prize. Then, I always regarded them as a superior class to which it was almost impossible to aspire. Now, suddenly, I find myself in that class, wondering whether they are so different. Did they obtain this great distinction – for indeed it is the greatest distinction a scientist can obtain – by deep thought, or did Dame Fortune play a part? We all know that chance, fortune, fate, or destiny – call it what you will have played a considerable part in many of the great discoveries in science. We do not know how many, for all scientists who have hit on something new have not disclosed exactly how it happened. We do know, though, that in many cases, it was a chance observation that took them on a track that eventually led to a real advance in knowledge or practice. This is especially true of the biological sciences, for there we are dealing with living mechanisms about which there are enormous gaps in our knowledge”.

__

A tradition of innovation

In our next installment, we will examine the history of lysozyme at Bioseutica Group®, sharing our part in this 100-year story. Join us then.

References

- Allison VD. Personal recollections of Sir Almroth Wright and Sir Alexander Fleming. Ulster Med J. 1974;43(2):89-98.

- Sir Alexander Fleming Nobel Prize Banquet speech - 1945

100 years of Lysozyme

2022 marks 100 years since news of Lysozyme’s discovery reached the Royal Society. Let us take you on the journey of this 100-year story: